Digging for Gravel – Part 2

I was intermittently aware of mom riding next to me in the hearse, of the siren blaring, of her calling out directions to the driver, a very nervous Mayfie, who was called in to drive at the last minute because John, the undertaker, was engaged in something else, something probably involving a dead body. Mayfie, who had no medical or emergency care training, kept glancing back where I lay moaning on the floor, right where the casket usually sat, as he tried to grasp the directions my mother shouted up to him. Mom later said she was nearly as worried about Mayfie getting us to the hospital in one piece, thirty miles away, as she was of my injuries. The interstate recently opened and he had never driven on it before and didn’t know the exits or the hospitals location in relationship to the new expressway. I doubt if he drove the hearse to the hospital much, and today, I even wonder how he obtained his driver’s license. But in a small town, back in the late 1950’s, standards were more flexible.

His real name was Mayford, and he was a large, big bellied guy who shuffled around town with a goofy smile. He knew everybody and heard lots of things going on in our small town, though his accuracy in repeating what he heard may have been questionable at times. He lived with his old maid sister who kept an eye on him. He mowed grass, shoveled walks and did odd jobs for businesses and people. Plus, he assisted the undertaker with loading and unloading the caskets, directing parking at funerals and driving the hearse to the cemetery, one mile south of town. He took much ribbing and teasing, but, in his good-natured manner, seemed to accept his lot in life with easy grace. In today’s world, he might be in a sheltered workshop or an adult group home; definitely not driving a hearse with people in it, dead or alive. But, back then, in small towns, most accepted the responsibility of looking after several characters of limited abilities in their midst. And everyone prayed like hell that John was available to drive the hearse, especially if you weren’t going to the cemetery!

In 1959, Clarksville did not have an ambulance or EMT’s. Those days were still in the future for small rural towns. There was no 911 system; only dial phones were available and party lines were still common. The fire department consisted of local men who volunteered and met twice a month to check the trucks and equipment and do some training before playing Ping-Pong. Their job was to put out fires as best they could. It was not to haul kids who had been blown off the top of a truck to the hospital. Eventually, a school mate and her husband, along with several other citizens, were instrumental in upgrading the volunteer fire department to one with trained EMT’s, an ambulance and a new fire house.

###

I was in a haze the first two or three days of my five-day hospital stay. I was somewhat aware of my parents taking turns sitting by my bed. With four younger siblings at home, I can’t imagine that they stayed there around the clock after the first night, but do recall one of them being there frequently, usually Dad. One night, a brown skinned nurse in her starched white uniform came in my room to check me over. She was beautiful, slightly plump, lots of curves and had a beautiful voice with a different accent. Ever so groggy, I looked up at her and asked, “Are you Hawaiian?”

She and Dad roared with laughter. “No, I’m not Hawaiian.” Then putting her hands in the air, she started dancing and swaying her hips. “But I can do a Hula for you anyway.” I had rarely seen an African American and never that close.

After five days of trying not to cuss as the nurses debrided my back, lying in bed on my stomach, and missing my buddy’s, I was more than ready to get home. Word traveled fast and my friends on their bikes were waiting as we pulled into the driveway. Upon my exit from the car, I gingerly climbed the front porch stairs, grabbed my bike and headed toward the stairs, ready to join them. My dad usually tried using humor to correct his brood. He did not this time. With a stern look, he quietly, but ever so firmly, said, “Son, put the bike back. You are not riding it for at least a week. You have a concussion. Now talk to your friends for a few minutes then get in the house and rest.” It was the voice I didn’t argue with and my friends soon vanished.

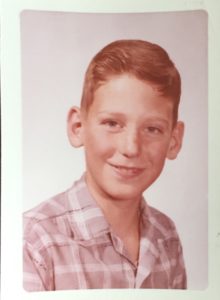

I recovered. Soon I ran my paper routes, cussed with my friends, discovered body hair sprouting in weird places, rode my bike all around our metropolis of 365 people and started 7th grade. My being a novelty soon ceased. I lived, it was just another kid thing, like a broken arm or appendicitis. No big deal. I had scars for many years. My lower back bothers me, but I don’t know if it’s a result of the fall or just hypochondria. Some of my friends and family frequently wondered aloud if my brain ever fully healed, but I managed to make it through college, hold a job, raise kids and pay taxes, for whatever that’s worth. I never drove a hearse, but I have driven a seventy-two-passenger school bus with a canoe trailer hooked on behind it through national forest two-track roads to unload and pick up canoeists. Neither my mother nor father ever mentioned hearing me cuss. And I have never asked.

While I was in college, my parents and siblings moved from Michigan to the state of Wyoming. Years later, my niece, who grew up in the West, married a man back in Clarksville and they bought a beautiful old brick farm house with a garage that sat next to a gravel road. The same garage whose shade I don’t remember borrowing back in 1959.

And finally, all these years later, I can still see that nurse with the wonderful accent dancing the hula.

She is still beautiful.

And still Hawaiian.